In her landmark 1967 essay “The Aesthetics of Silence”, Susan Sontag introduced the concept of silence as a language. “Consider the difference between “looking” and “staring”.

A look is (at least, in part) voluntary; it is also mobile, rising and falling in intensity as its foci of interest are taken up and then exhausted. A stare has, essentially, the character of a compulsion; it is steady, unmodulated, “fixed”. Traditional art invites a look. Art that´s silent engenders a stare. In silent art, there is (at least in principle) no release from attention, because there has never, in principle, been any soliciting of it.”

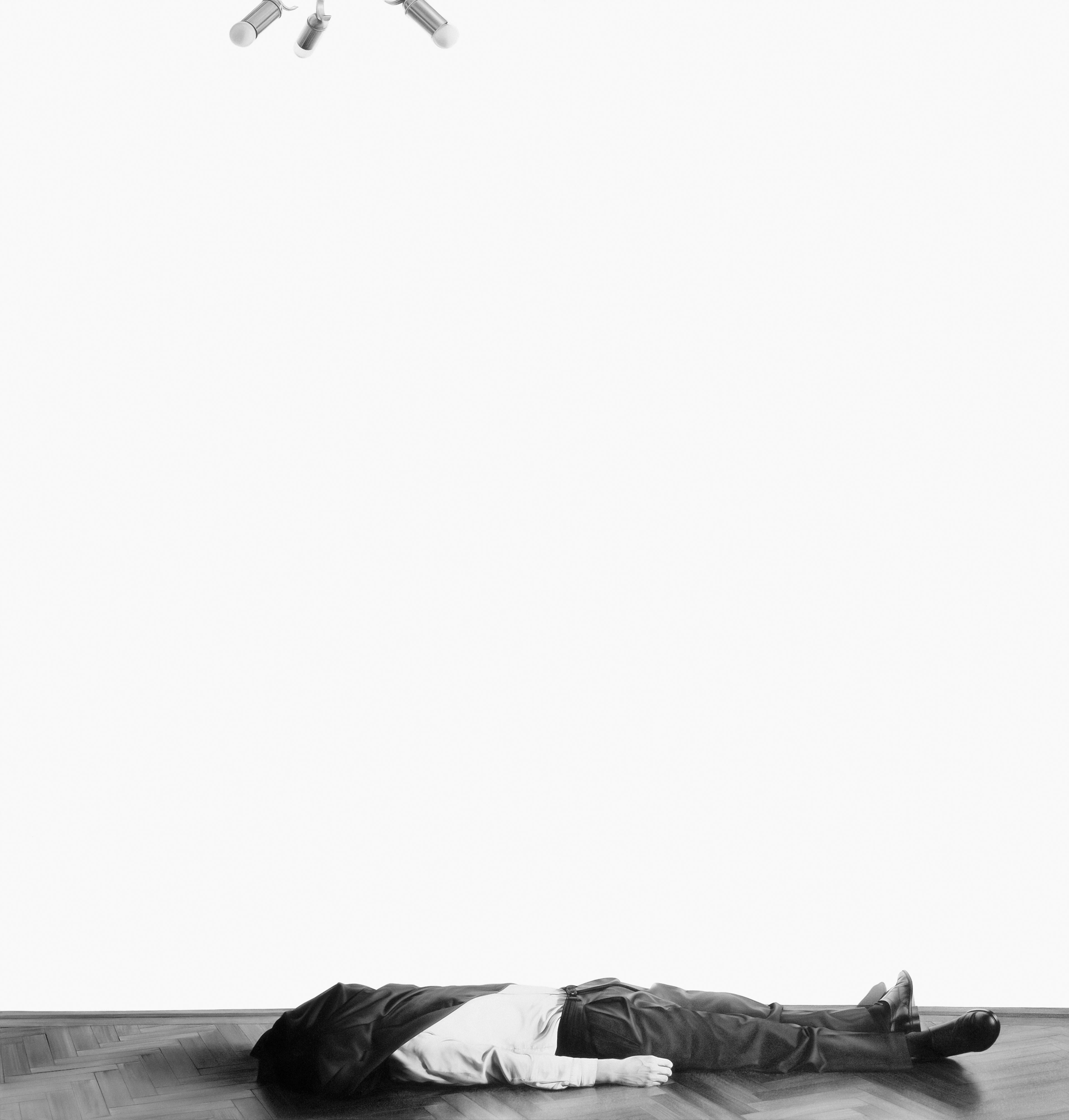

The paintings of Drago Persic, one comes to realise, require an unusual amount of time. They are reluctant to reveal themselves, to reveal the nature or conclusion of the larger narrative of which they each appear to be part. The viewer can simply move on, none the wiser, or stay and try to make sense of what is happening. There are clues which can be pieced together, like documents of a crime scene, but not enough to be sure of what they mean. One is asked somehow to fill in what is not there, to stare into those passages of painted silence, those spaces in between thick with suspense, and to find something on which our imaginations can take rest.

Any thread that begins to take shape does so in our own minds, anything romantic or sinister, harmless or harmful, that we might perceive is no more than that: a perception. We are players in quiet drama whose storyline the artist only barely suggests. Persic‘s careful arrangement of props, often isolated in sparse and unfamiliar settings to provide stimulus for our thoughts, has interesting parallels to something the Polish philosopher Roman Ingarden referred to within literature as Unbestimmtheitsstelle: a certain deliberate vagueness, which the reader (or in this case viewer) should interpret in his or her own way.

In some of the paintings it seems as if something might be about to happen, in others that it has just happened. Seldom do we register something still in process of happening. This strange, metaphysical duality is an important feature of the artist‘s work. A good many of his compositions have dislocated foci of attention: a chair turned toward the wall several feet from a light, or a girl with her back to an untidy sofa. It is this constant switch of attention, while never quite releasing it, that implies movement and the progression of a narrative. An interest in dichotomy, the natural world‘s own process of self-division and contradiction, can also be read in the artist‘s studies of leaves and branches.

Persic acknowledges and makes use in his painting of a number of devices more commonly associated with related media. The inclination to crop and extract details of larger scenes can be attributed to photography, which as a studio aid provides the primary source material for his work. It introduces a further degree of complexity, and a mechanical sense of perspective to compete with those both real and painterly. Perhaps more importantly, it contributes in large part to the silence and mystery that lies at the heart of his work. Painting, David Hockney once said, has layers of time in it. What a photograph does is fuse object and field by suspending both in time, trapping them together in a single, frozen moment. This moment is then itself suspended from the temporal continuum. Hence the stage curtain, a motif which recurs frequently in Persic‘s work. Time behind a curtain can also be frozen; one moment it is ours, then next it is not.

The artist‘s interest in the history and techniques of cinema is also apparent in his work. As with photography, it contributes both to the construction of the paintings and to their atmosphere. His narrowing of the focus onto small, singular objects set within larger situations – a light fixture, a plant or the foot of a curtain – is somehow the inverse of Hitchcock‘s device of leading with the detail before panning out to the whole. The reappearance of similar or identical objects in different paintings in turn gives weight to the suggestions that somehow this is all connected, as if we were passing through a series of different rooms or recalling the flickering memories of a dream. In these recent works the artist‘s palette is restricted to black, white and a series of greys made from mixing them, while his line is precise and dispassionate, detached even. The decisions behind their various compositions are thereby exposed, their apparent simplicity gradually giving way to a noted complexity. They are, in a certain sense, more credible. While the paintings seem at first glance to carry the immediacy of a photographic image, they are by no means read with the same speed. The measured and deliberate stillness with which they have been planned and executed successfully slows down our consumption of the image.

In the space between presence and absence, what we can see and what we can‘t, lies a vast arena for interpretation. It is here that the paintings of Drago Persic come to life.

Jasper Sharp

Published 2007 by enholm engelhorn galerie

Künstlermonografie

ISBN 978-3-9501358-1-7